The Vice and The Fool

Dr Eleanor Rycroft

Merry Report is the first nominated ‘Vice’ on the title page of a printed play. However, the line between the Vice of the late medieval and early Tudor drama, and the Fool of the later sixteenth century stage, is not always easy to determine, largely because they share many of the same performance tactics. The sixteenth century Fool is also influenced by the court jester – a figure licensed to prick pomposity and make jokes at the expense of power since the Middle Ages. Robert Armin’s portrayal of Shakespearean fools such as Touchstone, Feste, Thersites and Lear’s Fool, are all examples of licensed fools. That Armin drew upon the history of fooling in his performances, and particularly upon the career of Henry VIII’s jester, Will Sommers, is made clear in his 1600 text, Foole Upon Foole. So how might we tell the difference between the Vice and the Fool? Here is a list of some of the characteristics to consider:

Vices

Vices were figures from the medieval morality play and the folk drama. In the morality play, vices were the embodiment of evil and tempted the protagonist towards his downfall, often helped by the fact they were in the protagonist's service. The Vice, however, might be a specifically Heywoodian creation, and one which developed into the ‘fool’ or clown’ of the later Tudor drama.

Director Greg Thompson on Merry Report

As Peter Happé notes, Vices share common behaviours:

- They mock the church and priests

- They dance

- They are bawdy and focus on the lower half of the body, revelling in sex and excrement

- They engage in comic weeping

- They are interested in money

- They explain to the audience (in fact, they are characterised by their special relationship to the audience and their controlling of stage action)

- They announce their comings and goings

- Related to this is the “marvellous journey” the Vice undertakes, as when Merry Report’s tells the audience about his travels on his return to the stage.

Actor Danny Scheinmann on the debate over Merry Report as Vice

Vices also confound language, engaging in puns, bawdy, babbling, alliteration and repetition in a way which undermines the linguistic order.

The Vice exists on the margins of the play, between the actors and audience, and in an undefinable relationship to time and space. They confuse their name and origins. Merry Report says, “I am I per se I” and that he is, “A poor gentleman who dwelleth hereby” (104, 108) – like other stage Vices, he is trying to obscure his identity. This factor helps to narrow down Iago as a Vice figure because of his quibbling self-desciption in Othello: “I am not what I am.”

Elements of The Vice’s dialogue may have developed from the ancient tradition of ‘flyting’, wars of words involving the abuse of others – does this explain the argument between the Laundress and Merry Report at the end of their scene?

Fools

Fools could be ‘natural fools’ (‘simpletons’ and the disabled) or ‘artificial fools’ – versatile and gifted performers, like the celebrity clowns Will Sommers, Richard Tarlton, Will Kemp and Robert Armin.

In fiction, wise fools recognised their own weaknesses and desires, while pointing out the same in others. However, tricksters or evildoers did not recognise their own weaknesses and desires, despite pointing out those of others. Merry Report is often seen as a wise fool.

Real life jesters trod the fine balance between pleasing and displeasing their monarch-patron. In 1535, the Imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, wrote that Henry VIII had almost killed his fool for calling Anne Boleyn a “concubine” and their daughter, Elizabeth, a “bastard”. The notion of the fool’s licence to speak is therefore precarious. They were not always granted the freedom to rail unchecked.

Fools wore either the motley we associate with jesters, or looked tattered and tramp-like. The latter would probably have been the appearance of Merry Report, given his reference to “frieze” (134) – a coarsely-woven, woollen cloth, most likely a long, battered overcoat.

Is Merry Report a Vice?

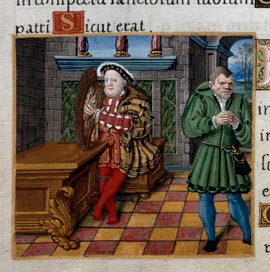

King Henry VIII as David, seated with harp, in an interior with his jester, William Sommers; illustrating Psalm 52

King Henry VIII as David, seated with harp, in an interior with his jester, William Sommers; illustrating Psalm 52Image taken from Psalter of Henry VIII.

Originally published/produced in 1530-1547.

This question of whether Merry Report’s function is to undo the moral order of The Play of the Weather provoked quite a debate on the Staging the Henrician Court website. Peter Cockett felt that Merry Report’s behaviour made him very much the stage Vice, but his role should be interpreted in line with the tradition of court fools and jesters. He contended that although Merry Report says he is a ‘gentleman’, this would have been understood by the audience to be a lie (as Jupiter indicates when he says that Merry Report’s appearance “bringeth witness nay” (109) to such an assertion of status). The lie might be signified by the fact that he wears motley, a “sure sign of his double dealing nature”. Moreover, Merry Report brings fun and comedy to The Play of the Weather. Cockett argued that, “all Merry Report’s actions are motivated by a desire to make merry” – a desire to entertain which is the province of the court fool.

Greg Walker agreed with this analysis, writing that Merry Report is devoid of a “moral compass”, and that the indifference required of him as a servant was also intrinsic to the amoral essence his character;

Tom Betteridge and Eleanor Rycroft discussing Merry Report

...he is indeed indifferent - he doesn't care, which makes him a potentially very bad royal servant, but quite a good vehicle for satire, exposing the weaknesses and foibles of everyone, including the King.

Tom Betteridge, however, disagreed with the idea that Merry Report has no moral compass, despite his repeated claims that this is the case. Betteridge said that the evidence for this lies in the fact that;

He does treat different characters differently and these differences seem, at least potentially, to be based on a set of moral judgements. Merry Report's interactions with The Boy and The Laundress are different to those he has with The Gentleman and The Merchant. Indeed I would suggest he is particularly critical of The Gentleman and The Merchant because of their hypocrisy.

So Merry Report’s treatment of The Gentleman and The Merchant derives from the fact that they hypocritically claim to be acting in the interests of the commonwealth, when in fact they act for their own self-interest.

On the basis of these forum debates, we decided to further investigate the performance possibilities for Merry Report in the workshops of March 2010.

Below are two videos of the workshops from March 2010. In one video, Danny Scheinmann plays the scene for narrative by privileging the storytelling, and in the other he revels in the exuberance of language, is shown to be both inside and outside of the staged action, comically weeps and displays an excessive interest in money. He also produces a more physical performance and returns once again to the alliterative list of place names – a dramaturgical convention particularly favoured by Heywood. It is perhaps this marvellous journey which is one of the most enduring features of the late medieval and early Tudor Vice, appearing in The Pride of Life, Mundus et Infans and Hick Scorner, and alluded to in post-Heywoodian dramas such as Like Will to Like and Horestes. However, this form of verbal virtuosity is no longer in evidence as the Vice transforms into his connected theatrical personae of the fool during the later part of the sixteenth century, and can therefore be seen as a distinctive aspect of the early English drama.

Video 1 : Workshop Performance - The Appointment of Merry Report - Version 1 of 2

Video 2 : Workshop Performance - The Appointment of Merry Report - Version 2 of 2

References: Peter Happé, ‘The Vice and the Folk-Drama’, Folklore, Vol. 75, No. 3 (Autumn 1964), p161-93.