Merchants

Dr Eleanor Rycroft

The early modern period was one of enormous economic and cultural upheaval as Britain changed from a feudal society to one governed by trade, commerce and the beginnings of capitalism. The transformation had started in the Middle Ages and by the early 1500s the merchant class had emerged as a social group with their own interests and cultural concerns. The Play of the Weather is not the only interlude to include a merchant among it's cast of characters; another play sometimes attributed to Heywood, Of Gentleness and Nobility, also portrays a merchant. The changeful social relations of the period are made manifest in this work, as the three characters - a plowman (standing for Britain's agricultural heritage), a knight (representing the chivalric and aristocratic tradition of rule) and a merchant (an agent of the new economic order) - debate the basis of honour and virtue in a nation which is in flux.

Merchants therefore seem to be represented as an emergent system of authority, considered against traditional forms such as the aristocracy, feudal labourers and the Church. Indeed, Merry Report mistakes The Merchant for a member of the clergy when he initially enters the playing space, saying, "Mayster Person [Parson], now welcome by my lyfe!" (329). Yet the satire and specific meaning of this line proved elusive for the production team, as Tom Betteridge and Eleanor Rycroft discuss in Video 1.

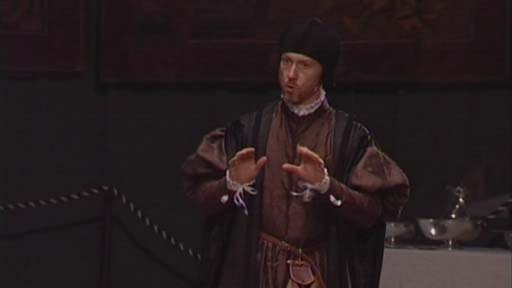

Video 1 : Tom Betteridge and Eleanor Rycroft discussing The Merchant

So the lineaments of attachment between the space and structure of the court and the role of The Merchant proved one of the most difficult elements of the play to fathom. If the Church was losing power and influence during the first half of the sixteenth century and the City and market was gaining it, then The Merchant seems to gesture towards the rise of the secular and socially mobile in Tudor society at this time. But how does he 'fit' into dominant structures of power? How would a member of the emergent mercantile class relate and react to the space of the Great Hall, for instance, and how does his lack of understanding of the correct protocol regarding tips at the end of the scene affect audience response to his character?

There seems to be uncertainty surrounding courtly ceremony and The Merchant in The Play of The Weather - whether he should be allowed access to Jupiter and on what basis. This is textually indicated by the fact that while Merry Report is requesting if Jupiter will see The Merchant, the character moves from his correct place by the time of Merry Report's return, leading him to exclaim, "Why, where be you? Shall I not fynde ye?" (343). In our production we made sense of this moment by showing The Merchant becoming engrossed in the splendour of the Great Hall, as if this was a space to which he was not accustomed.

Video 2 : Theatrical Director Gregory Thompson on The Merchant

Yet the court also had to rely on merchants for the exotic goods, foodstuffs and fabrics which materialised their magnificence, and mercantilism was on the rise throughout the century. Merchant activity was often allied with banking and also usury: issues that would become more and more significant for the male courtier when the expensive lifestyle that he was expected to lead was increasingly subsidised through financial credit that he could not necessarily repay. We can perhaps see some of this ambivalence in the representation of The Merchant in The Play of the Weather; a necessary and important member of the commonwealth, but one whose growing cultural prominence was beginning to impinge on the court in ways with which they were not wholly comfortable. The Director, Greg Thompson, speaks about this issue - demonstrating how the representation of The Merchant compares with that of The Gentleman who has immediately preceded him on-stage, and arguing how his inclusion in the play undermines the function of the aristocracy who comprised the play's original audience: See Video 2.

However, there is an interesting postscript to The Merchant's supplication to Jupiter and this concerns the tipping of Merry Report, the courtier-servant. The Merchant seems unclear of the protocol of this moment, indeed that there is any etiquette to be observed. Perhaps this is the moment where the aristocracy who are being criticised are able to have the last laugh in the scene. The Merchant as a character might be worldly in his travels, but is depicted as unworldly in his knowledge of the power structures with which he interacts.

The Merchant's claim to be acting in the interest of the Commonwealth is not necessarily as altruistic as it appears either. The Merchant's mention of "Syo" where he hopes to have sailed before "myd-Lente" (385) is an interesting reference to the island of Chios in the Aegean Sea - a precedent for the East India Company in that it was ruled by the Maona Guistiniani, Genoese traders who were granted the right for the revenues of the island by the Republic of Genoa between 1347 and 1566. The Maona Guistiniani therefore effectively managed the island, and exploited Chios as a point in the trade route between East and West in order to compete with the Venetians who had a stronghold in that region. In controlling the resources and revenues of Chios, the company shareholders of the island became very wealthy.

Chios, or "Scio" also appears in a work by the Henrician Revels producer, Clement Armstrong, entitled 'A treatise concerninge the staple and the commodities of this realm’, in which he writes of the English Merchant, John Crosby, a fifteenth century importer of Italian textiles and:

ane [one] of the first that advernturid into Spayn, so as upon a fourty four yere ago Spayn was callid a farre adventure, and abowt a thirty six yere agoo was first occupieng to Turkye, Scio, and to all thos partes, alle which now are cowntid but as comon recourses, every nacion owt goyng a nothyr, every to oversayle by yonde other to seke syngularite.

(1924, p91)

There is a sense in Armstrong's treatise, which was produced sometime between 1519 and 1535, that mercantilism and the granting of trade monopolies to merchants is not always having the positive effect which The Merchant foregrounds in his suit. Armstrong laments that in Calais, where English 'staplers' or traders in wool held the monopoly on all wool exports, there are more staplers than there is wool: “As all inordinate companyes made by mens wisdome, encreasyng into syngler weale, distroyeng comon weale, hath but a beeng and endyng for a certayn age” (ibid.). Contrary to The Merchant's argument in The Play of the Weather therefore, Armstrong evokes a commonwealth in which merchants are able to amass individual fortunes, and presents a view of English trade which favours the interests of a small group rather than the whole country. While it remains incredibly difficult to reconstruct the exact significance of The Merchant within the sphere of the play, it could be that some of this contemporary feeling is being ironised by The Merchant's claim to be acting in the interests of all.

References:

Clement Armstrong, 'A treatise concerninge the staple and the commodities of this realm', in Tudor Economic Documents, Vol III, Ed. Tawney, R.H., and Power, E (Longmans, Green and co.,1924).